3. Developing standards for fortified rice: country examples

In comparison with staple foods such as wheat/maize flour, salt and edible oil, which have been fortified for decades, rice is a more recent addition to the portfolio of staple foods that can be fortified to address nutritional deficiencies. In most settings, fortifying rice should benefit from the regulatory framework already in place for large-scale food fortification and the experience gained in developing current or past standards.

In Asia and the Pacific, three countries mandate the fortification of rice with micronutrients: Papua New Guinea, the Philippines and Solomon Islands. Fortified rice is provided in social safety net programmes in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Malaysia and Nepal. It is also available in retail markets through a voluntary, market-based approach in Bangladesh, India and Myanmar, and in Bangladesh workplace benefit programmes offer fortified rice.

In recent years, several countries in Asia have been through the process of developing new standards for fortified rice. These include Bangladesh, India and Timor-Leste, which now offer a good benchmark for other countries embarking on rice fortification. While India and Bangladesh already had standards in place for other foods (including wheat flour, salt and edible oil), Timor-Leste developed a multiple-staple fortification standard process for four foods at the same time: rice, wheat flour, oil and salt.

These experiences are relevant to all countries in the region regardless of their expertise and experience in setting food fortification standards. They are described in the following section and have subsequently been used to develop a recommended standard approach to setting rice fortification standards for other countries.

Bangladesh (2014–2015) The Government of Bangladesh initiated the standards development process to support the launch of fortified rice into national food systems. Standards were developed simultaneously with acceptance trials and effectiveness studies. These three elements formed the basis of the evidence required before fortified rice could be launched into food systems.

An iterative process led by BSTI and facilitated by WFP The Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution (BSTI) led the process. WFP was asked to facilitate and coordinate the initiative based on its experience in leading the standard development process for wheat flour fortification and its credibility as a major distributor of rice through emergencies in the country.

BSTI started by forming a technical committee that was composed of regular members plus guest members such as international non-governmental organizations specialized in the field of fortification. The standards were developed during four different meetings held over some 12 months between the end of 2014 and 2015.

As the technical lead driving the process, it was important for WFP to have the necessary internal technical expertise to ensure credibility with partners and provide appropriate guidance. Technical staff were recruited to build expertise and capacity and to develop the initial standards based on standard operating procedures provided by BSTI.

Updating the standard

Over the years, practical experience revealed a number of weaknesses in the standard that was initially developed; this led to upgrading the standard in 2022, following the same process already described.

The update focused on two main points: 1) the addition of test methods to the standard, and 2) the addition of 30 percent overage for three of the micronutrients in the standard. The decision to add 30 percent to strengthen the existing standard arose after a retrospective study of traditional rice cooking methods in Bangladesh showed that rice is cooked in excess water which is discarded once cooking is complete, risking significant degradation/loss for three of the micronutrients.

Political game changer

One of the effects of the introduction of the fortified rice standard was that it replaced the compulsory wheat flour fortification programme. The development of the new fortification standard revealed that rice was better adapted to local consumption habits and was therefore more likely to deliver convincing results in the fight against micronutrient deficiencies.

Figure 2: Bangladesh journey

India (2016–2018)

Creating a rigorous overarching process

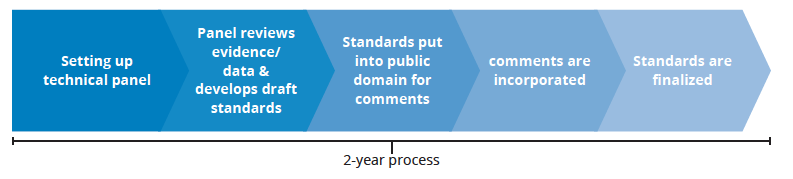

The Government of India wanted to reduce levels of anaemia in the country, hence its rice fortification initiative. It was led by the Food Safety Standard Authority (FSSAI) – hosted under the auspices of the Ministry of Health – and its scientific panel, which works on setting and updating food fortification standards. The scientific panel was tasked with developing the draft standards using recommended dietary allowances and available micronutrient deficiency data. The aim was to collect as much input as possible from external subject experts to ensure that standards were technically sound and in line with international guidelines. Comments were taken to the scientific panel and incorporated following technical discussions within the panel. The process lasted two years from development of draft standards and their operationalization in 2016 to their publication (gazetting) in 2018.

Experience has shown that it is important to ensure that members of such technical committees are

not only subject experts but that they are also motivated and informed of the benefits of developing such standards. This enables them to become strong advocates of the law once it is gazetted and implemented. A detailed description of the India rice fortification scale-up journey can be found in two documents (a) Journey of scaling up rice fortification Asia: Connecting food systems with social protection to enhance diets of those who need it most (8). (b) The proof is in the pilot: 9 Insights from India’s rice fortification pilot to scale approach (9).

Figure 3: India 2-year journey to rice fortification standard gazetting

Offering flexibility for expanded standards

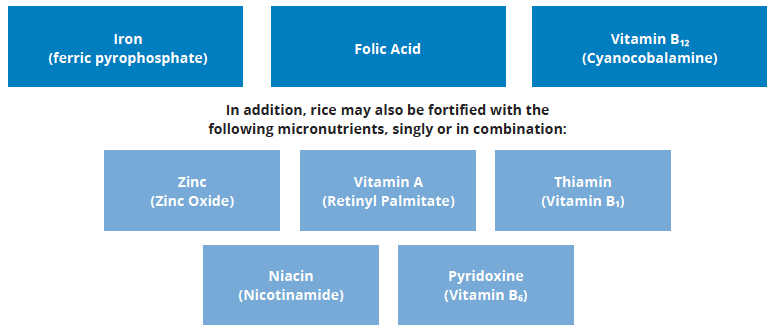

One of the original features of the Indian standard is that it proposed two lists of micronutrients: a blend that met minimum micronutrient criteria and another that included additional micronutrients, which would be voluntary. This flexibility was introduced so as not to overwhelm rice millers with a potentially expensive blend of micronutrients while ensuring that a minimum set of micronutrients were present in the rice (especially those targeted at addressing anaemia). When distributing fortified rice, the state and the private sector decide whether to use a formulation adding three mandatory micronutrients (iron, folic acid and vitamin B12) or a more comprehensive formula containing one or a combination of the following micronutrients: zinc, vitamin A, vitamin B1, vitamin B3 and/or vitamin B6.

Figure 4: Mandatory & voluntary micronutrients for rice in India

Timor-Leste (2021–present)

In Timor-Leste, where 70 percent of the food is imported, there was no regulatory framework until the country embarked on its journey to develop multiple standards simultaneously. Because their process started in 2021, Timor-Leste was able to leverage WFP’s expertise and experience gained in accompanying other countries in the region, resulting in the fast-tracking of the fortification standards adoption process. The process was extremely inclusive with external partners playing an important technical role, in particular the private sector which provided expertise and insights into the discussions and guaranteed the operational viability of the standards.

Developing a regulatory framework from scratch Unlike Bangladesh and India which had long-standing experiences of setting fortification standards, Timor-Leste was unique in that none of the country’s staple foods were fortified and they had never been through the fortification process. This created additional complexities, not least the need to justify such an intervention. WFP, with other partners, conducted a Fill the Nutrient Gap (FNG) analysis which recommended, among other things, the introduction of fortified

rice as an essential intervention for the country. In parallel, a rice landscape analysis and an acceptability trial were conducted. They provided evidence for the technical and logistical feasibility of fortifying rice.

The accumulation of this evidence led the Ministry of Tourism, Commerce, and Industry of the Government of Timor-Leste to ask WFP to support a food fortification programme in the country and to institute a legal and regulatory framework around the fortification of three staple foods: wheat flour, rice and edible oil.

A multisectoral approach

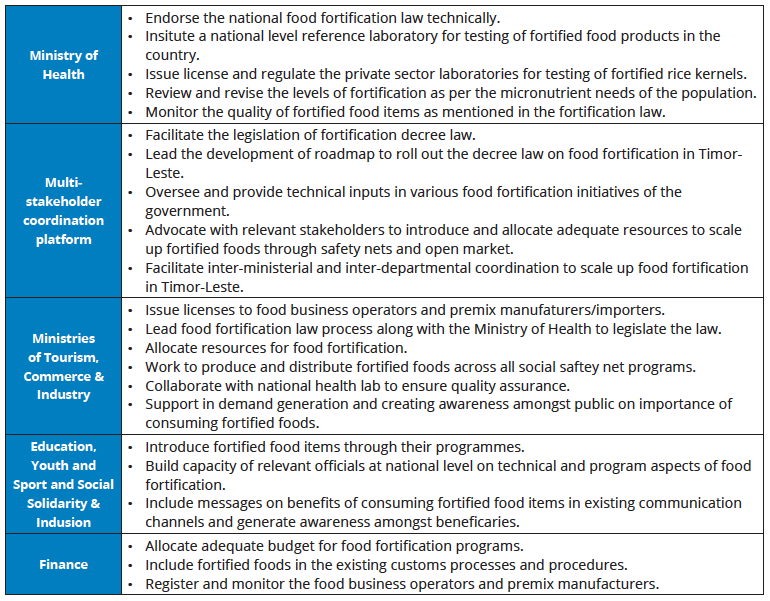

Developing food fortification standards is often led by Ministry of Health who reviews and revises the levels of fortification as per the micronutrient needs of the population and endorses the national food fortification law technically. While this approach has obvious advantages and rationale, a more holistic approach has been considered in Timor Leste with active leadership of additional stakeholders, in particular Ministries of Industry, Tourism and Commerce.

Specific roles were assigned to different ministries which contributed to building accountability across the board. The specific roles and responsibilities of key ministries are detailed in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Roles of relevant stakeholders

This holistic approach ensured that fortification standards were not only health-focused but also considered the broader food value chain and economic implications, resulting in a more comprehensive and effective fortification strategy. Involving multiple ministries fostered cross-sectoral coordination and alignment of objectives. Ministries often have their unique priorities and goals. By engaging several ministries in the development of the standards, it became easier to align these priorities.

Relying on international methodologies

As Timor-Leste was new to the fortification of staple foods, the role of WFP and all the main technical stakeholders was important. WFP helped to put in place a consultative framework that enabled a technical consensus on the standards developed. Given the lack of experience nationally, the country used available evidence, data and internationally recognized methods, such as WHO/FAO guidelines on fortifying food with micronutrients. The estimated average requirement (EAR), recommended nutrient intake (RNI) and upper limit (UL) values from the guidelines were used to set levels for each of the selected micronutrients. Harmonization with regional and global standards and specifications was pursued through technical consultations with internal and external subject experts.

Defining a road map to implement the law Timor-Leste is in the process of finalizing and issuing the law and operationalization is yet to be realized. At the request of the government, WFP developed a road map to operationalize the law. It envisions a gradual adoption of the new standard to increase the percentage of rice to be fortified progressively over three years: from 25 percent in year one to a targeted 90 percent in year three for local rice, and from 50 percent in year one to 100 percent in year three for imported rice. This strategy enables industry to plan and adapt manufacturing processes and defray investment costs over a longer period.

Figure 6: Timor-Leste standard development methodology