Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

The FGD on Strengthening the Role of Private Sector Stakeholders in the Implementation of Mandatory Food Fortification in Indonesia, held at Harris Hotel Tebet on 13-14 November, highlighted the role and perception of the salt industry, as well as the industry's expectations of the government. Salt fortification has encountered many obstacles along the way, including the revocation of Permendagri 63/2010 to Permendagri 6/2018. In order to strengthen the salt iodization program, there are several things that are the focus of discussion.

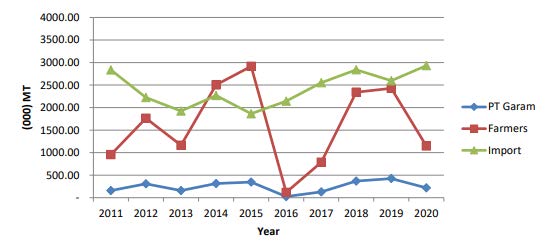

Mr. Budi Satriyono, representative of APROGAKOB, said that the existence of IKM salt producers who do not comply with the regulations and are not coordinated needs more attention. IKM or salt farmers have a significant contribution to the national salt supply. Based on the GAIN study (2021), in the period 2011-2020, PT Garam's contribution to the total salt supply was the lowest, while the role of imported salt increased and farmers' production fluctuated. Therefore, meeting the SNI requirements for SMI salt must be a concern in order to strengthen the salt iodization program. The quality of raw salt produced by farmers is generally considered to be below the Indonesian National Standard (SNI), with NaCl levels of around 80-85% and high levels of contaminants.

Figure 1. Salt supply from 2011-2020

Source: KFI (2019), KKP (2019), BPS (2020), Kemenperin (2021)Mr. Rozy Jafar of Nutrition International added that there is an element of politicization, which can be seen in the reluctance of producers to renew the license because the sanctions are the same for products that do not have SNI and those that have SNI but do not renew the license. In addition to the reluctance of producers to renew their licenses, the issue of the high cost of obtaining SNI is also an obstacle for small producers. GAIN Indonesia mentioned in its study that according to an informant who is a small-scale salt producer, the cost of obtaining an SNI certificate is Rp16 million to Rp19 million (including Rp4 million for a consultant), and the process takes about three months. The SNI certificate is valid for five years, but there is annual monitoring by LSPro. Another small-scale producer mentioned that the cost of obtaining an SNI certificate is IDR 12 million and the annual supervision fee is about IDR 6 million. These annual costs are considered expensive by small-scale producers (GAIN 2021).

The representative of UNICEF, Ms. Dewi Fatmaningsih, emphasized the need for a joint discussion among stakeholders on who has the authority to sanction salt companies that do not comply with the regulations. This is in line with the GAIN (2021) study, which found that in Indonesia there are monitoring activities at the production, market (pre-market and post-market) and household levels, but no follow-up corrective actions are taken after the assessment. The monitoring system should also include rapid analysis and dissemination of data to inform authorities of any necessary corrective action. Failure to take corrective action after monitoring can certainly undermine the salt iodization program. Therefore, sanctions and officials empowered to impose sanctions are necessary.

To strengthen the salt iodization program, it seems necessary to learn from China's success. The key to China's success, apart from the fact that salt is monopolized by the government, is massive socialization through various channels such as advertisements on public buses and in newspapers (Goh 2002). In addition, strict internal and external quality assurance tests are conducted at the production and wholesale levels, supported by the Surveillance System for Iodine Deficiency Disorders in China (CSSIDD) (Chen et al. 2014). Furthermore, the seriousness of the Chinese government in the success of the salt iodization program can be seen in the establishment of the "Salt Police" unit in 1994, with 25,000 officers, to enforce the salt monopoly policy and confiscate the circulation of non-iodized salt sold to the poor (Fackler 2002).

Regarding the availability of KIO3, Mr. Budi Puspo Hudojo of Kimia Farma (KF) said that KF's production is only about 20-25 tons per year. However, KF is committed to meet the domestic demand of fortified salt farmers. Mr. Adhi S. Lukman, representative of GAPMMI also emphasized the need to reactivate YAYASAN KEGIZIAN PENGEMBANGAN FORTIFIKASI PANGAN INDONESIA Komp. Bappenas A1 Jl. Siaga Raya, Pejaten Jakarta 12510, Indonesia Phone / 62-021-26966290 Email : kfi@kfindonesia.org Permendagri as a legal umbrella for local governments to activate the GAKY team. Mr. Akim Dharmawan from the Directorate of KGM Bappenas added that in the future, the LSFF Forum will be a forum to discuss problems, barriers and synchronization of food fortification programs (Rep: Rhm & Han; Ed: Elm & Roz).

Sumber Pustaka

KFI. 2019. Situation Analysis of Salt Sector in Indonesia. Jakarta : Indonesian Nutrition Foundation for Food Fortification (KFI).

KKP. 2019. Annual Report. Jakarta:DJPRL.

BPS. 2020. Impor Garam Menurut Negara Asal Utama, 2010-2019.

Kemenperin. 2021. Industri Garam Konsumsi dan Program Iodisasi Garam di Indonesia. Jakarta: Kementerian Perindustrian

GAIN. 2021. Review of Salt Iodization & Rice Fortification in Indonesia.

Goh CC. 2002. Combating iodine deficiency: lessons from China, Indonesia, and Madagascar. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 23(3):280-291.

Chen Z, Hongmei S, Li M, Gu Y, Lu ZX, Suying C. 2014. China: Leading the way in sustained IDD elimination. IDD Newsletter. 42(2):1-5. Available at: nl_may14_web.indd (ign.org).

Fackler M. 2002 Nov 24. Chinese Provinces Police Salt of The Earth. Los Angeles Times. [diakses 2022 Agustus 27]. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-nov-24-adfg-salt24-story.html